John Warriner

John Warriner

When practicing taijiquan forms (sets, 套路 tàolù), we pass through a series of postures as we move – think of them as waypoints. Generally speaking, these postures have names known to us in their original Chinese, translated to our native language, or both. I think it is reasonable to ask whether knowing the name of a particular posture affects how one interprets the changes flowing in the move.

Consider the Chen style taijiquan move Jīn Gāng Dǎo Duì (金刚捣碓). The English translation I’m familiar with is “Buddha’s Warrior Attendant Pounds Mortar.” The image I have associated with the move from early on in my practice is of a great warrior smashing a mortar with or without a pestle. (捣 dǎo means pound or smash, 碓 duì means mortar). Why one would do such thing I have never decided. I have no doubt that the source of my mental image was mainly watching the thunderous stomps of the taiji masters. Still, the name, I believe, subtly influenced my execution of the move.

There are historical reasons for confusing taijiquan terms. For one, martial arts in China, particularly family arts like Chen Family Taijiquan, were passed down through personal instruction consisting primarily of hands-on corrections and oral instructions which referenced the postures, moves, and principles by name. Because very little was written down and because of the profusion of local and regional dialects and languages in China, posture names were sometimes heard differently by different students. So, even among Chinese practitioners there was, and continues to be, a diversity of posture names.1 Sometimes the received translation/interpretation of the Chinese posture names is misleading simply because, for non-Chinese, there is no cultural context in which to understand them. Literal translation from the Chinese by early non-Chinese taijiquan practitioners sufficed to give the postures understandable and pronouncable names.

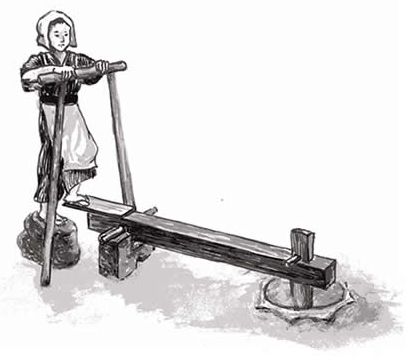

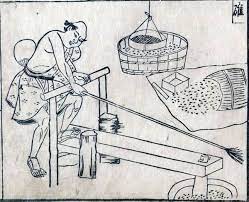

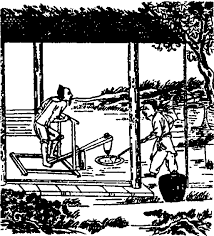

When I looked into the phrase “dǎo duì”, I discovered that the term as it appears in the posture name ( 捣碓, Term 1) is homophonous with another pair of characters, 蹈碓, Term 2. Both of these terms are used to refer to the use of a mortar and pestle, but the first character in Term 2 means to step on or tread. So Term 2 seems to refer to working a foot-operated mortar and pestle, called a shíduì (石碓). As it happens, a person operating this type of machine assumes a posture very similar to the taijiquan movement in question. Holding on to the machine with the hands, the operator raises the heavy stone pestle by pressing down with one leg and then releasing it by drawing the leg up allowing the pestle to drop into the large stone mortar to grind whatever grain is therein, a motion very similar indeed to that of Buddha’s Warrior Attendant Pounds Mortar.

In light of the above, I think it is very likely that the name of this posture was taken from the operation of the shíduì and not from the image of a great Buddhist warrior pounding/smashing a mortar. Therefore, I would like to offer another translation/interpretation of the name for this signature Chen style taijiquan movement – “Master Works the Mill”. As for the subtle influence the posture name may have on my practice, I can say that thinking of pressing down with the foot to raise the heavy pestle is quite a bit different than stomping, and the lifting of the foot now has more of a release feeling. Of course, regardless of what it is called, I will continue seek the real essence of this move from my teacher.

Below are some images of the foot-operated grinding machines.